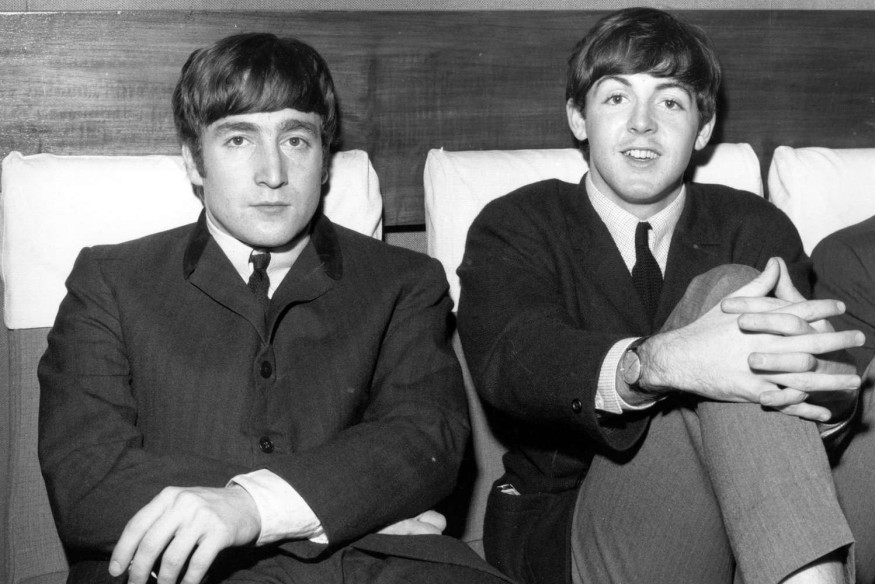

John Lennon’s complex personality resurfaces in a shocking story from his early years in New York — a night when things got out of control at a party. According to producer Jack Douglas, the legendary Beatle once pulled out a knife in an attempt to stop a heated political argument, revealing a raw and emotional side of his nature that few people ever saw

The incident, which took place in the early 1970s, was recently recounted by Douglas during an interview on Billy Corgan’s podcast The Magnificent Others. Douglas, who worked closely with Lennon in the final years of his life, recalled the chaotic night — a mix of alcohol, loud slogans, and rising tempers that spiraled unexpectedly.

Lennon had attended a New York party with activist Abbie Hoffman and other figures from the counterculture movement, many of whom were known for their radical political rhetoric. As Douglas explained, the energy in the room became increasingly tense. The guests were shouting revolutionary slogans, including “Off the pig,” a phrase commonly used by militant groups like the Black Panthers, referring to police officers.

Lennon, who had already begun to distance himself from violent activism, grew visibly uncomfortable as the conversation turned darker. Douglas described the scene vividly: Lennon, frustrated and drunk, got up, walked into the kitchen, grabbed a knife, and shouted at one of the loudest guests that if she wanted violence, he would show her what it really meant. The outburst silenced the room instantly.

Douglas clarified that Lennon never intended to hurt anyone — his reaction was emotional rather than threatening. It was a spontaneous, dramatic way to shut down the escalating aggression in the room. “He scared everyone,” Douglas said. “The woman stopped shouting, and we left soon after. John wasn’t a violent man; he just couldn’t stand the hypocrisy of people preaching peace through violence.”

At that point in his life, Lennon was deeply involved in social movements but increasingly disillusioned by their contradictions. He and Yoko Ono had moved to New York seeking artistic freedom and had become friends with activists like Hoffman and Jerry Rubin. They had convinced him to perform at a rally supporting writer and activist John Sinclair, who had been imprisoned for marijuana possession.

However, Lennon soon realized that his celebrity was being used for political gain. According to Douglas, he often complained that these people were “crazy” and manipulative. “He wanted peace, not revolution,” Douglas added. “He didn’t want to become a political pawn — he wanted to be an artist who stood for honesty and change through music, not aggression.”

The story reflects a key tension in Lennon’s life: his struggle between activism and his desire for peace. While he supported progressive causes, he rejected the idea of fighting hate with hate. The knife episode, however shocking, serves as a metaphor for his frustration with the violent rhetoric of the time. Lennon wanted to stop the noise, not fuel it.

Douglas, who was with Lennon in the studio on the day he was killed, remembers a man who had long since made peace with his inner battles. By 1980, Lennon was optimistic, creative, and looking forward to the future. He often spoke about spending more time with his son, Sean, and working on new music. “He was happy,” Douglas recalled. “He was finally at peace with himself.”

At the time of his death, Lennon was collaborating with Douglas on new recordings. His renewed energy and sense of clarity marked a different era in his life — one driven by love, family, and art rather than politics or controversy. Douglas once asked him what made a great song, to which Lennon replied, “Tell the truth and make it rhyme.” It was a simple philosophy, but it captured everything about him: sincerity, emotion, and a deep understanding of what it means to connect with people.

This story, unsettling as it may sound, underscores Lennon’s passion for authenticity. He wasn’t a saint, nor did he try to be. His art was raw because he was raw — honest to the point of discomfort, unwilling to hide behind carefully crafted images. In that moment at the party, his outburst wasn’t about violence; it was about standing against it, even if his way of doing so was flawed.

Lennon’s relationship with Yoko Ono and his immersion in New York’s activist circles shaped much of his worldview, but ultimately, he refused to be boxed into any ideology. His message was simple yet radical: peace is not passive. It requires courage, confrontation, and self-awareness.

Decades later, Lennon’s legacy remains timeless. From his early Beatles years to his solo albums, his work continues to echo messages of truth, love, and nonviolence. The story of that night in New York serves as a reminder that even the most peaceful voices are born from struggle — and that humanity, with all its contradictions, was always at the heart of John Lennon’s music.

Today, his songs still resonate because they come from that same raw honesty. Lennon wasn’t preaching perfection; he was exposing the flaws of a world — and a self — that could only find light through acceptance. His legacy is more than just melodies and lyrics; it’s the lasting belief that peace begins within, even in moments of chaos.